Preparing for Launch

An important part of being able to mine the flight data for insight is being able to determine which part of the data to mine. We want to do this programmatically, rather than relying on hand-labelling all the data.

In the last post, I found that the flight data should be able to help approximate wind speed and direction. However for this to work, we have to make sure we’re not feeding junk data into the model (such as when my vario starts beeping while I’m flying down the highway in my car). We also want to focus on the periods where the glider is in free flight, that is, not under tow from an aircraft or ground-based winch.

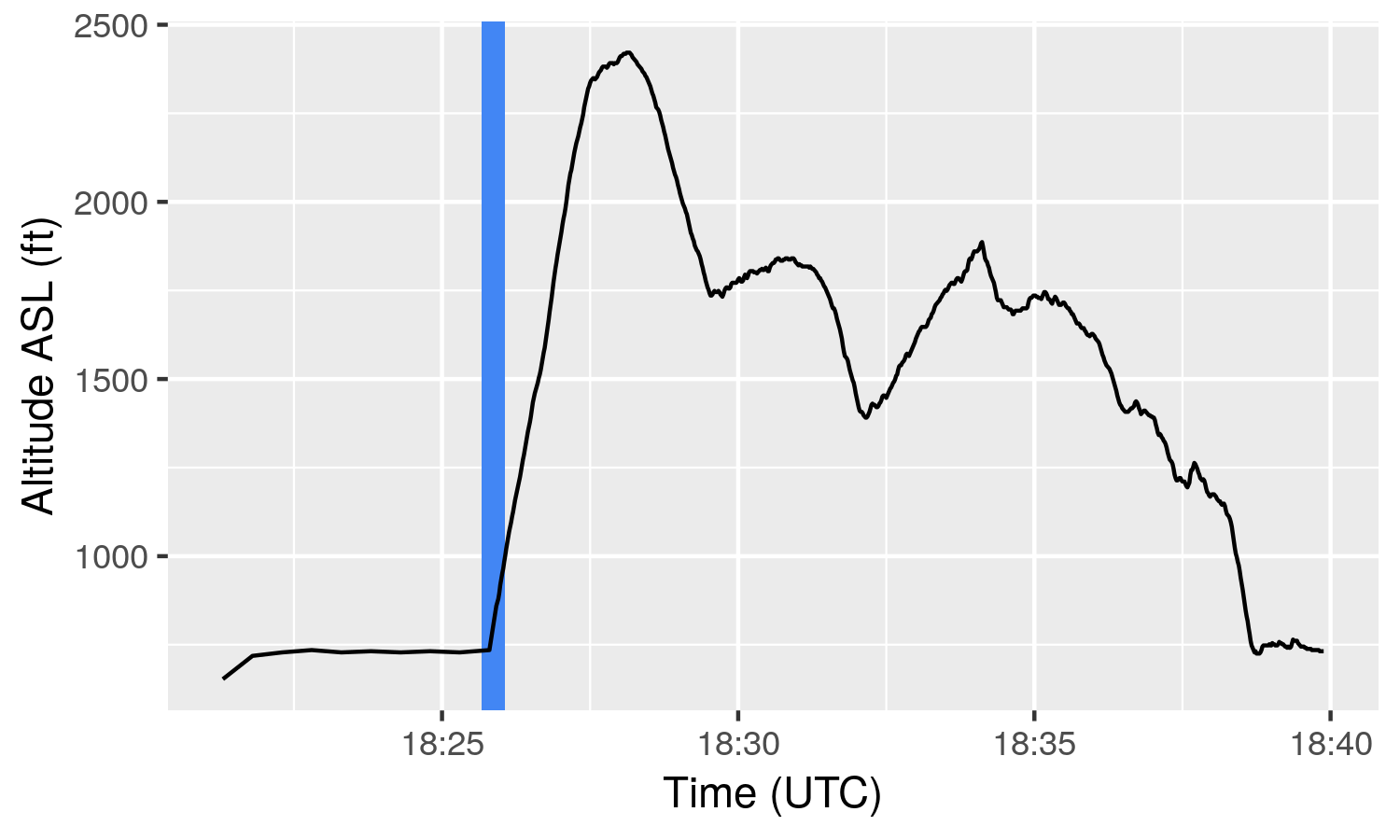

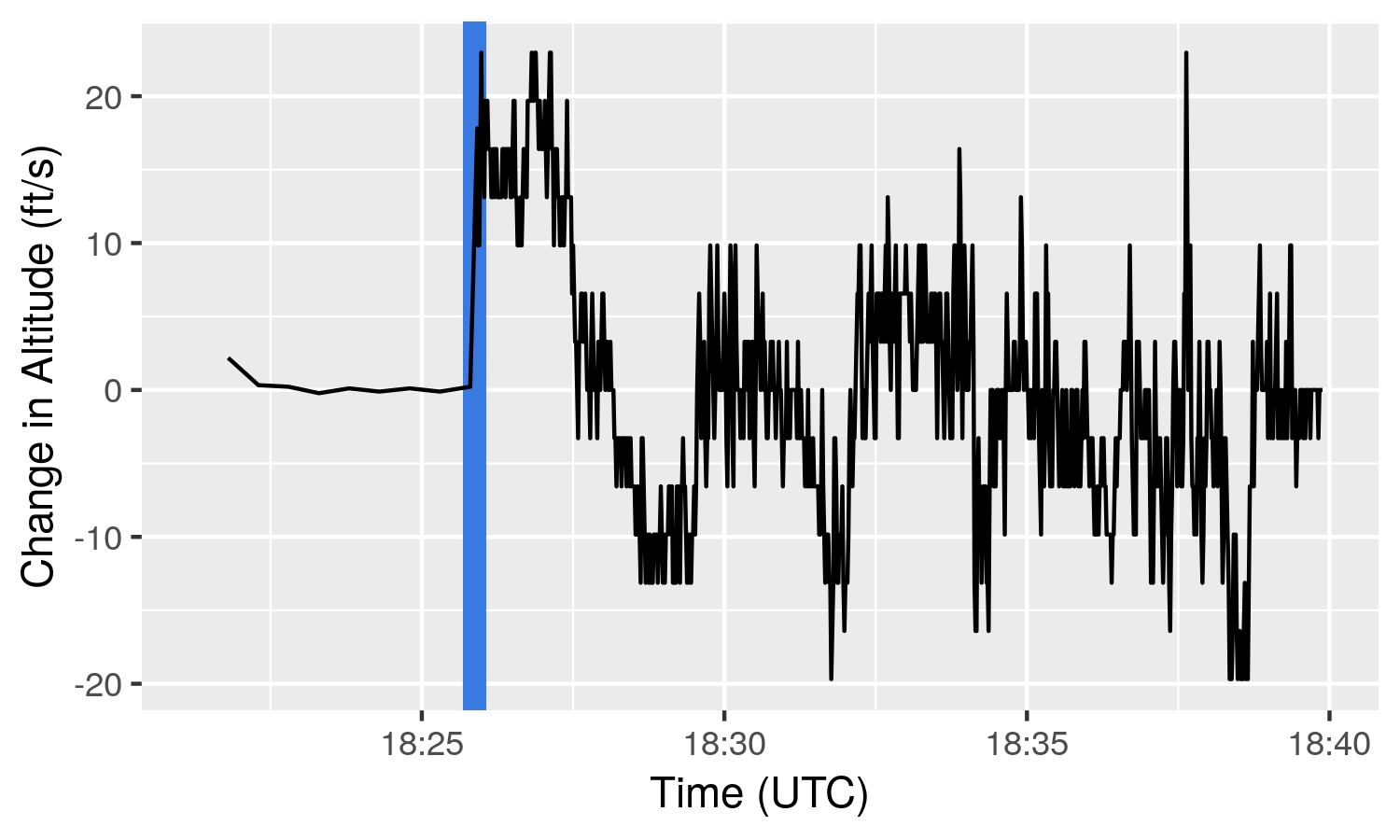

For starters, let’s just focus on narrowing down flying versus not flying. We could use an abrupt increase in altitude to identify the start of a tow.

However, on some fraction of hill and cliff launched flights, no lift gets encountered. In these types of flights, there will be no increase in altitude for the entire flight, but we still want to capture this flight data. Conversely, we don’t want to capture the increase in altitude during the ride back to the top of the hill as a flight.

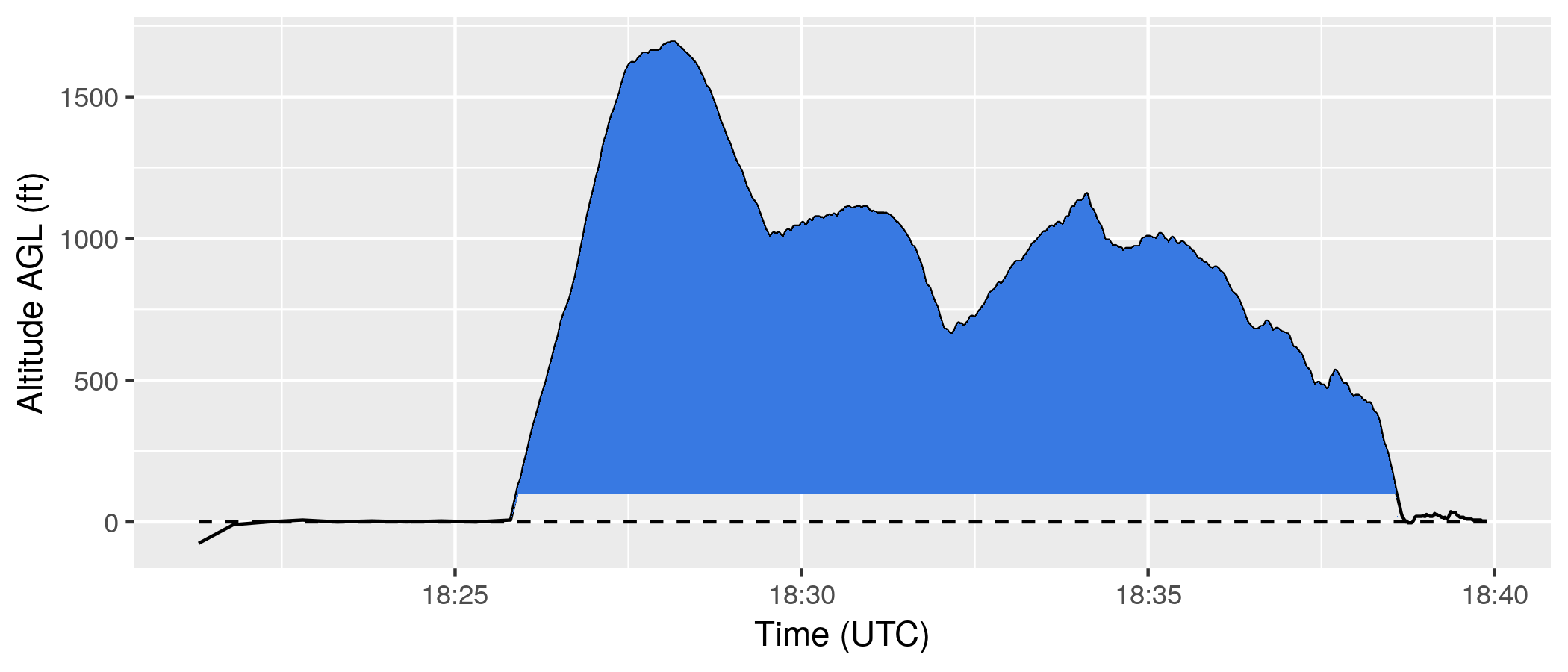

Without getting too technical, a good indication of whether or not you are flying is to compare your location to the location of the ground under you. If the ground is significantly below you, this is good evidence that you might be flying.

\[ me_{elevation} >> ground_{elevation} = me_{flying} \]

There are fringe cases which violate this such as low-res or bad GPS data, driving over suspension bridges, falling, etc., but in general, this is a good heuristic.

This also solves the problem of identifying hill launches that never increase in altitude, since as the glider moves away from the hill, the distance above the ground increases. Unless the pilot is @wolfgangsiess, pictured below.1

My vario records altitude above sea level (ASL). A relative altitude is zeroed before flight to provide altitude above ground (AGL), however, this value is only displayed during flight and not recorded. Further, for a number of reasons such as pilots forgetting to zero their altitude and the fact that ground elevation changes with location, we can’t depend on recorded AGL values.

We have a reliable latitude and longitude telling us where we are on earth, so we should be able to use this to figure out the ground elevation.

There are a number of APIs on the web for determining elevation from location, such as Google’s Elevation API.

It requires a Google Cloud Platform account (free to create but requires credit card in case you exceed minimum quotas) in order to create a key for your API calls, but is fairly straight-forward to use.

You POST an http request with latitude, longitude, and your key…

curl -XPOST 'https://maps.googleapis.com/maps/api/elevation/json?key=<secret-api-key>&locations=46.129960399999995,-81.4175856'

…and get a JSON response with ground elevation information in meters.

{

"results" : [

{

"elevation" : 392.0873107910156,

"location" : {

"lat" : 46.12996039999999,

"lng" : -81.4175856

},

"resolution" : 38.17580795288086

}

],

"status" : "OK"

}

There are also client libraries for a number of different programming languages.

The Elevation API can be used to calculate AGL by subtracting the resulting elevation from the altitude given by the vario. This can be used to plot the AGL for a flight, showing the height above ground throughout. Now we have a common frame of reference regardless of the ground elevation. When the AGL is above some threshold, it’s probably because we are flying.

However, the Elevation API comes with several limitations. Firstly, it costs money. After the first 40,000 searches per month, searches are charged at a rate of $5 USD per 1000 searches. That is about $0.28 USD per hour of vario data at a rate of one search per data point. Additional use such as identifying surface features like nearby hills and mountains would result in even more calls. These costs could add up.

This problem can be easily solved by pre-fetching a grid of elevations and latitude-longitude coordinate pairs and caching them for later use except that, no it can’t because that violates the Terms of Service which prohibits pre-fetching and caching. So a lot of API calls would be required to keep the in-flight ground elevation up to date. There’s strategies we could use to reduce the number of calls, but there are also a number of other restrictions on the API usage, such as

- “digitizing, or creating other datasets based on Google Maps Content”, and

- “[using] Elevation API data on a map that is not a Google map.”

In particular, the condition below seemed particularly draconian for our use case.

3.2.4 Restrictions against Misusing the Services

(i) No Use for High Risk Activities. Customer will not use the Google Maps Core Services for High Risk Activities.

Given all these limitations, I didn’t even bother actually using the Elevation API for the plot above and faked it instead. I then moved on to look for better alternatives to finding elevation.

This led me into the world of GIS, and gave me the opportunity to work with a dataset produced by a vehicle with significantly different flight characteristics than a hang glider.2

This will be the subject of the next post.

- https://www.instagram.com/wolfgangsiess/ [return]

- Referring to the inferior glide ratio of the space shuttle, with a lift-to-drag of 4.5. [return]