Introduction to Data Project

Overview

Welcome to my hang gliding data project!

The goal of this project is to use the latest data science techniques on large sets of hang gliding flight data. The major objectives are to:

- Data mine large sets of flight data to understand hang glider flight dynamics, thermal generation, and thermal development

- Identify the geographical, weather and atmospheric, glider, and pilot input characteristics that contribute to successful flights

- Ultimately, develop a machine learning algorithm to provide in-flight recommendations to help locate thermals (and avoid sink).

But…why?

What’s the point of all this? Or, for the uninitiated, what’s a thermal anyways?

Hang gliders pilots (and others, such as paraglider pilots) rely on several techniques to remain aloft while in free flight. These include thermals, ridge lift, and convergence lift.

Thermals are rising columns or bubbles of air. They are caused by solar radiation heating the ground, which causes this air near the ground to become warmer. Eventually, a mass of the warmer air breaks free, rising through the cooler air above, somewhat like a bubble rising in a lava lamp.

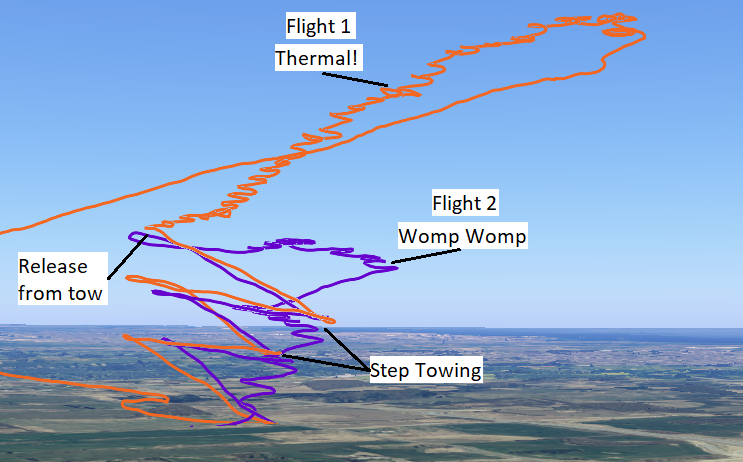

Thermals can be used to extend hang glider flights significantly. The image above shows two flights from the same day. In the first flight, I entered a thermal straight off of tow, and was able to circle up 1,500 ft, doubling my altitude. In the second flight, I only found weak lift, and was barely able to maintain my altitude, before coming down.

While centering in a thermal is largely a matter of experience and technique, the challenge is locating the thermals. Unless there is physical evidence of a thermal (such as seeing another pilot successfully achieving lift), they are effectively invisible.

Further, since there is a large rising volume of air, there is also typically descending air, or “sink”, in the proximity of large thermals to fill in the displaced mass. Even long flights can be cut short by searching for thermals and finding nothing but sink.

A system which improves the reliability of finding thermals (and avoiding sink) would benefit both novice pilots (by extending their flights and experience) and advanced pilots (who may need to find elusive lift while travelling 100’s of km’s cross country). Further, the predictions made by such a system may lead to insights and improve the understanding of thermal generation and development.

The Data

Most hang glider pilots fly with a variometer (or vario) on their glider. Varios record GPS position (latitude, longitude, and sometimes altitude), and barometric pressure (which is used to solve for altitude). Varios are typically configured to emit audible tones based on changes in the rate of descent, emitting high pitched beeps when lift is encountered. Sometimes, the vario will connect to an airspeed sensor to provide airspeed data, however, this is less common.

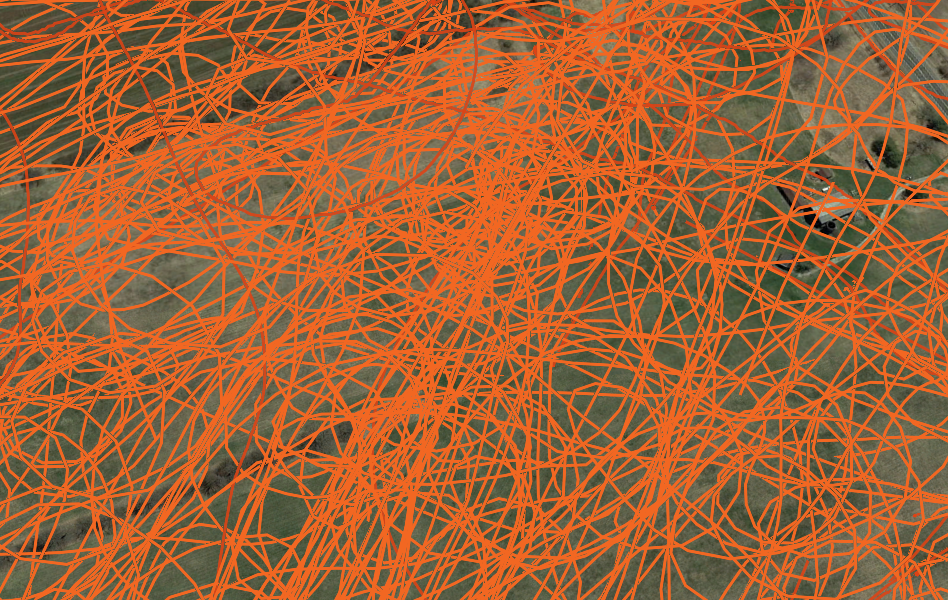

The primary dataset would be the recorded flights of hang glider pilots, as logged by their vario. The images below show 48 flights at High Perspective Hang Gliding in Ontario, Canada.

This relatively small dataset already covers a considerable range of weather and flight conditions, however, the intent is to collect as much flight data across as many locations, conditions, and gliders as possible, as more data will lead to stronger and more robust findings. If you would like to contribute your flight data to this project, please get in touch!

You can find the project source code on Github.

My goal is to report progress and findings on this site, so stay tuned!